Patient-Related Factors

Lack of knowledge about the disease and the reasons medication is needed, lack of motivation, low self-efficacy, and substance abuse are associated with poor medication adherence (Krueger et al., 2005; World Health Organization, 2003).

A person's perception of the danger posed by their disease may affect adherence to treatment. Older adults with chronic diseases that pose no immediate limitations or have few or no symptoms - such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or osteoporosis - may dismiss the importance of medication adherence. When medications are slow to produce effect, as with antidepressants, a person may believe the medication is not working and thus become nonadherent. On the other hand, a person's belief that a medication will work or is working is directly related to treatment adherence, as is the ability to manage side effects and a positive attitude (Krueger et al., 2005).

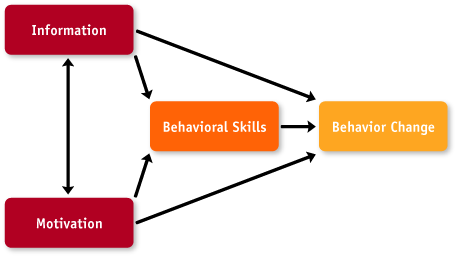

It is well known that a person's knowledge, motivation, and attitudes toward medication therapy can significantly influence medication adherence. The World Health Organization has proposed a foundational model for medication adherence that is based on three factors: information, motivation, and behavioral skills (self-efficacy). Interventions based on this model have been effective in influencing behavioral change (World Health Organization, 2003).

Adherence and nonadherence are behaviors. Information is a prerequisite for changing behavior, but in itself is insufficient to achieve this change; motivation and behavioral skills are critical determinants (Figure 3). Information and motivation work largely through behavioral skills to affect behavior; however, when the behavioral skills are familiar or uncomplicated, information and motivation can have direct effects on behavior (World Health Organization, 2003).

Information is the basic knowledge about a medical condition, which may include how the disease develops, its expected course, and effective strategies for its management; as well as specific information about the medication prescribed (World Health Organization, 2003).

People should have knowledge and understanding of the following:

- Information about the disease and consequences of not treating it

- Information about the treatment options

- Name of each prescribed medication, what it is supposed to do, and why it is needed

- Side effects of each medication and what to do if they occur

- How and when to take each medication, how much to take, and for how long

- What to do if a dose is missed

- What food, drinks, other medicines, or activities should be avoided while taking the medication

- How the medicine should be stored

- Whether the medication can be refilled, and if so, how often.

In addition, any special techniques or devices for administering the medication (e.g., the use of syringes, inhalers, suppositories, eye drops, or patches) should be explained and demonstrated. Older adults should be asked about any concerns they have about using their medicine.

A person's knowledge of their health condition and treatment can be assessed by measuring their health literacy and medication knowledge. The specific assessment tools are described below, and instructions for use are found in the Assessment Tools section.

Health Literacy Assessment - Health literacy is the ability to read, understand, and act on health information in order to make appropriate health decisions. Poor health literacy results in medication errors, impaired ability to remember and follow treatment recommendations, and reduced ability to navigate within the health care system. The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine, Revised (REALM-R) is a brief screening instrument used to assess a person's ability to read common medical words (Bass et al., 2003). It is designed to identify people at risk for poor literacy skills.

Medication Knowledge Assessment - The Medication Knowledge Assessment is used to determine a person's knowledge about their medications and ability to read and comprehend information necessary for appropriate medication use. Information from the Medication Knowledge Assessment can serve as the basis for a focused knowledge improvement plan.

Motivation encompasses personal attitudes towards the adherence behavior, perceived social support for such behavior, and the person's perception of how others might behave. Motivation has been found to be a key factor in promoting adherence to chronic therapies (World Health Organization, 2003). A person's motivation to adhere to a prescribed treatment is influenced by their beliefs regarding their medical condition, the value they place on following the treatment regimen, and their degree of confidence in being able to follow it. A person who believes that their condition is serious, that they will develop serious consequences if the condition is left untreated, and that the medication will be effective in treating their condition and preventing complications may be more likely to adhere to the treatment regimen (Vermiere et al., 2001).

Motivation encompasses personal attitudes towards the adherence behavior, perceived social support for such behavior, and the person's perception of how others might behave. Motivation has been found to be a key factor in promoting adherence to chronic therapies (World Health Organization, 2003). A person's motivation to adhere to a prescribed treatment is influenced by their beliefs regarding their medical condition, the value they place on following the treatment regimen, and their degree of confidence in being able to follow it. A person who believes that their condition is serious, that they will develop serious consequences if the condition is left untreated, and that the medication will be effective in treating their condition and preventing complications may be more likely to adhere to the treatment regimen (Vermiere et al., 2001).

Motivation and readiness to change are fundamental to long-term alteration of behavior (Nichols-English and Poirier, 2000). Changes in behavior are frequently based on weighing the positive and negative aspects of the change. Change will likely take place when the person sees the positive aspects of making the change and there are no or few barriers to making the change. However, if the real or perceived barriers or negatives of making a change outweigh the positives, change is unlikely to occur.

A primary reason people are not motivated to engage in a behavior - such as taking medication - is that they are ambivalent. When ambivalent, people generally do nothing. In regard to medications, people may be ambivalent about (Berger et al., 2004):

- Necessity - the person is not sure they really need the medication or that they have the diagnosed condition.

- Effectiveness - the person is not yet convinced the medication will work.

- Goals of therapy - are not clear or are not important to the person.

- Cost - of the medication is more than expected or more than the person can afford.

To overcome ambivalence, older adults must have the information necessary to determine that the benefits of taking the medication outweigh the cost or barriers (Berger et al., 2004).

The assessment of motivation can help gauge the likelihood that the person will adhere to a given treatment regimen. Motivation is determined by measuring the person's willingness or readiness to change, and the level of their social support.

Readiness to Change Assessment - The Readiness-to-Change Ruler is used to assess a person's willingness or readiness to change, determine where they are on the continuum between "not prepared to change" and "already changing", and promote identification and discussion of perceived barriers to change. The Readiness-to-Change Ruler can be used as a quick assessment of a person's present motivational state relative to changing a specific behavior, and can serve as the basis for motivation-based interventions to elicit behavior change, such as motivational interviewing.

Motivational interviewing is an approach, first reported in the addiction literature, to improve adherence (Miller and Rollnick, 2002). The process is used to determine a person's readiness to engage in a target behavior - such as medication taking - and then applying specific skills and strategies based on the person's level of readiness to create a favorable climate for change. See the Facilitating Behavior Change section for additional information on readiness to change and an introduction to motivational interviewing techniques.

Social Support Assessment - A person's perception of and need for a social support network can be assessed with the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire, an eight-item instrument to measure the strength of the person's social support network (Broadhead et al., 1988).

Self efficacy is a person's belief or confidence in their ability to carry out a target behavior and the extent to which the behavior is actually carried out correctly. Self efficacy includes ensuring that the person has the specific behavioral tools or strategies necessary to perform the adherence behavior (World Health Organization, 2003). Self efficacy is a significant predictor of medication adherence (National Quality Forum, 2005).

| BARRIER | STRATEGIES |

|

Knowledge

|

Identify "knowledge gaps"

Provide information where gaps exist

Confirm understanding; have person repeat the information

Demonstrate any special techniques for use of devices for administering medication

Ask about any concerns the person has about using the medicine

Provide appropriate written information

Follow up for reinforcement of the information provided

|

|

Motivation

|

Use motivational interviewing techniques for people in the precontemplation and contemplation stages of change

"Roll" with resistance

Involve person in problem solving

Provide information and alternatives

Express empathy

Avoid argumentation

Develop discrepancy between the person's behavior and important personal goals

Involve family members

Refer to support group

|

|

Self-Efficacy

|

Use motivational interviewing techniques to enhance the person's confidence in their ability to overcome barriers and succeed in change

Recognize small positive steps the person is taking

Use supportive statements

Help person set reasonable and reachable goals

Express belief that person can achieve goals

|

Substance abuse, particularly of alcohol and prescription drugs, among adults aged 60 and older is one of the fastest-growing health problems facing the country. Problems stemming from alcohol consumption, including interactions of alcohol with prescribed and over-the-counter medications, far outnumber any other substance abuse problem among older adults. Rates for alcohol-related hospitalizations among older adults are similar to those for heart attacks (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998).

The abuse of narcotics is rare among older adults, except for those who abused opiates in their younger years. Prescribed opioids are an infrequent problem as well; only two to three percent of noninstitutionalized older adults receive prescriptions for opioid analgesics, and the vast majority of these older adults do not develop dependence (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998).

Although little published information exists, experts report that a far greater concern for drug misuse or abuse is the large number of older adults using prescription drugs - particularly benzodiazepines, sedatives, and hypnotics - without proper physician supervision (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). A large share of prescriptions for older adults is for psychoactive, mood-changing drugs that carry the potential for misuse, abuse, or dependency.

Older persons are prescribed benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium, Xanax, Ativan) more than any other age group, and North American studies demonstrate that 17% to 23% of drugs prescribed to older adults are benzodiazepines (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). The dangers associated with these prescription drugs include problematic effects due to age-related changes in drug metabolism, interactions among prescriptions, and interactions with alcohol. Benzodiazepines, especially those with longer half-lives, often cause unwanted side effects that affect functional capacity and cognition, which place the older person at greater risk for falling and for institutionalization. Older adult users of these drugs experience more adverse effects than do younger adults, including excessive daytime sedation, lack of muscle coordination, delirium, and cognitive impairment.

Identification of substance abuse among older adults should not be the purview of health care workers alone. Leisure clubs, health fairs, congregate meal sites, Meals-On-Wheels, and senior day care programs provide venues in which older adults can be encouraged to self-identify for problems with alcohol or prescription medications. Friends and family of older adults and staff of senior centers, including drivers and volunteers who see older adults on a regular basis, are usually familiar with their habits and daily routines, and can interject screening questions into their normal conversations with older adults.

Comfort with this line of questioning will depend on the person's relationship with the older person and the responses given; however, anyone who is concerned about an older adult's drinking practices or possible medication misuse can try asking direct questions, such as those listed in Table 4. Nonmedical caretakers, volunteers, and aides may opt to ask only the four CAGE questions for alcohol problems, reproduced in Figure 4 (Ewing, 1984).

If the questioner suspects that prescription drug abuse may be occurring and the older adult is defensive about his or her use, confused about various prescription drugs, seeing more than one doctor, or using more than one pharmacy, a clinician should probably be notified to probe further. Other warning signs of problematic alcohol or prescription drug use that may emerge in conversation and should prompt a referral to a clinician for a more in-depth screen or assessment are listed in Table 5.

DRINKING PRACTICES AND MEDICATION USE

| DRINKING PRACTICES |

|

“Do you ever drink alcohol?”

“How much do you drink when you do drink?”

“Do you ever drink more than four drinks on one occasion?”

“Do you ever drink and drive?”

“Do you ever drink when you’re lonely or upset?”

“Does drinking help you feel better [or get to sleep more easily, etc.]? How do you feel the day after you have stopped drinking?”

“Have you ever wondered whether your drinking interferes with your health or any other aspects of your life in any way?”

“Where and with whom do you typically drink?” (Drinking at home alone signals at-risk or potentially abusive drinking.)

“How do you typically feel just before your first drink on a drinking day?”

“Typically, what is it that you expect when you think about having a drink?” (Note: Positive expectations or consequences of alcohol use in the presence of negative affect and inadequate coping skills have been associated with problem drinking.)

|

| MEDICATION USE |

|

“What prescription drugs are you taking? Are you having any problems with them? May I see them?” (This question will need to be followed by an examination of the actual containers to ascertain the drug name, prescribed dose, expiration date, prescribing physician, and pharmacy that filled each prescription. Note whether there are any psychoactive medications. Ask the patient to bring the drugs in their original containers.)

“Where do you get prescriptions filled? Do you go to more than one pharmacy? Do you receive and follow instructions from your doctor or pharmacist for taking the prescriptions? May I see them? Do you know whether any of these medicines can interact with alcohol or your other prescriptions to cause problems?”

“Do you use any over-the-counter drugs (nonprescription medications)? If so, what, why, how much, how often, and how long have you been taking them?”

|

| 1. | Have you ever felt you should Cut down on your drinking? | YES | NO |

| 2. | Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? | YES | NO |

| 3. | Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking? | YES | NO |

| 4. |

Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (Eye opener)? |

YES | NO |

Scoring: Item responses on the CAGE are scored 0 for “no” and 1 for “yes” answers,

with a higher score an indication of alcohol problems.

A total score of 2 or greater is considered clinically significant.

|

Brief intervention techniques have been used to reduce alcohol use in older adults. Research has shown that 10% to 30% of nondependent problem drinkers reduce their drinking to moderate levels following a brief intervention by a physician or other clinician (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). A brief intervention is one or more counseling sessions, which may include motivation-for-change strategies; education, assessment, and direct feedback; contracting and goal setting; behavioral modification techniques; and the use of written materials such as self-help manuals. All of these activities can be conducted by trained clinicians, home health care workers, psychologists, social workers, and professional counselors.

If the older problem drinker does not respond to the brief intervention, two other approaches - intervention and motivational counseling - should be considered. In an intervention, which occurs under the guidance of a skilled counselor, several significant people in a substance abuser's life confront the individual with their firsthand experiences of his or her drinking or drug use (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). Motivational counseling acknowledges differences in readiness to change and offers an approach for "meeting people where they are" that has proven effective with older adults (see Motivational Interviewing in the Facilitating Behavior Change section).

Because so many problems with prescription drug abuse stem from unintentional misuse, approaches for responding differ in some important respects from treatment for alcohol abuse and dependence. Issues that need to be addressed as part of treatment include educating and assisting older adults who misuse prescribed medications to comply consistently with dosing instructions, providing informal or brief counseling for persons who are abusing a prescribed substance with deleterious consequences, and engaging drug-dependent older adults in the formal treatment system at the appropriate level of care. In addition, it is important to understand how practitioners' prescribing behavior contributes to the problem so it can be addressed both with clients and uninformed health care practitioners in the community.

For some older adults, especially those who are late-onset drinkers or prescription drug abusers with strong social supports and no mental health comorbidities, the above approaches may prove quite effective, and brief follow-up interventions and empathic support for positive change may be sufficient for continued recovery. There is, however, a subpopulation of older adults who will need more intensive treatment. Despite the resistance that some older problem drinkers or drug abusers exert, treatment is worth pursuing. Studies show that older adults are more compliant with treatment and have treatment outcomes as good as or better than those of younger persons (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998).